With his back to Christi, Bishop stood knee-deep in the bone-stiffening current of Blue River, clenching his fist around his fishing pole. Christi ran her flower petal fingertips down the separations of his neck again. Instead of jerking from her, this time he swatted her away.

“Why you doin’ that?” she asked.

“Done told you we gotta quit each other.”

“But you came like you have all summer.”

“I came to fish, to tell you to quit callin’ the house, showin’ up unannounced. We’re first cousins. Let’s leave it at that.”

On wobbled balance Christi dropped her fishing rod, forced her warm lips against Bishop’s ruggedly-aged warmth. Then took a breath and pleaded, “Don’t do this. I’ll kill her for you. No more Melinda. Just Christi and Bishop.”

Her words pulsed a threat within Bishop’s forty-plus years of understanding right from wrong. He’d have to use something more than words to end it.

Bishop dropped his pole. Exploded his catcher-mitt-palms against Christi’s ears. She gulped a scream. His fingers spread into her thick hair of black edged with pine needles of gray. Kicked her balance. Guided her beneath the current and straddled her chest. Christi’s legs splashed. Bishop’s hands swallowed her clawing hands that had sorted mail from 8-5 Monday through Friday at the Harrison County Post for twenty years. Pinned them to her throat. Watched bubbles explode into lost breath beneath the cold water. Telling himself he’d no other choice, she wouldn’t listen.

A vehicle came barreling down the gravel road from the valley above. Christi’s fight slowed just as the sound of the vehicle slowed. Steering squeaked. An engine grew silent. Bishop kept Christi pressed into the flat river rock with madness chewing through his bloodstream.

He thought a door slammed. But his hearing played tricks with the rushing sounds of his insides and the flowing river in which he sat. He heard boots kicking gravel, weeds and twigs snapping off in the distance, but he couldn’t be certain if they were distant steps or just nervousness maturing with the static-like silence within his eardrums.

When the cold current had numbed his grip to an ache and she was passive, he stood with her body floating to the surface. Her pits V-ed into his damp shins. He saw no movement along the weeded valley road above. Drug her to the riverbank. Pulled a tin of Shlitz from the six-pack that lay along the river’s edge. Popped it open. Downed it.

Wondering what to do with her body.

He smashed the beer tin and opened another. Took a long, hard sip, closed his eyes, shook his head and laughed. Felt the sensation from taking a life climb through his veins.

Standing over her, he took in the cellophane gaze of her open eyes. The shock that filed down her chalk-white cheekbones. The bruises already showing like ink smudges around her neck and wrists. The dampness of her flower print dress with two perfect circle-eight-shapes laying beneath. He told himself, “Beautiful even in death.”

Bishop stood, remembering how his father and he’d fished this area since he could string a pole and bait a hook. Remembering all of the largemouth bass, hand-sized blue gill and channel cat they’d caught. He pulled a smoke from his shirt pocket that wasn’t wet, along with a dry Ohio Blue Tip match. Knelt down, flicked a flame. Pulled an orange coal with his eyes following the current downstream. Blowing smoke from his lungs, it came to him like a vision from his Maker.

He walked up the dirt trail of boot prints that separated the wilted weeds littered with fish bones and rusted beer tins. Followed it up to the gravel of the valley road above where he’d parked his rusted Chevy. Opened the door, pulled the burlap sacks from behind the truck’s seat that he used for keeping the coons, rabbits or squirrels he shot during hunting season. Grabbed the rusted log chain. Pulled a pair of pliers from the glove box. A partial row of barbed wire from the floorboard. He glanced up and down the road for a parked vehicle, seeing nothing but gravel and trees with leaves turning the shade of pumpkins while his heart punched his eardrums.

Back down along the riverbank he filled the burlap sacks with flat flint and limestone river rock. Tied them shut. Forced them beneath Christi’s damp dress. Coiled the wire around her frame. Twisted it tight to her flour-tinted flesh with pliers. The barb broke her flesh open. Formed tiny rivers of red. He reinforced the weight with the rusted log chain he wrapped around her, connected the hooking ends into one another. He drug her stiff frame downstream like a small johnboat until he got to the fishing hole from his youth, where Bishop remembered his father telling him as they stood knee deep, staring into the dark green hole that melded into black, that if someone ever wanted to hide something, this’d be the place.

He pushed her into the thick blackness. Dove in, guiding her sinking body, the cold water lock-jawing his bones, burning his bends and pivots. All the way to the bottom where his hands felt, pushed and tucked her away beneath a smooth cliff of river rock. A space made for a human outline. With eyes closed he pushed her body till he felt rock meet his shoulders and face, both arms extended into the unknown void, her remains never to be found like an antique lost in an attic.

He surfaced with his mind aching for air, lungs tight and fast expanding. Feeling as though he was breathing through a tractor’s brake line.

Bishop sat on the bank of river sand and scattered flint. Clothes dripping in the evening sun. His teeth chattering. Telling himself she’d left him no other choice.

Somewhere up on the road above he thought he heard the slamming of a vehicle’s door, and the faint cranking of an engine that disappeared down the distance of the valley.

*

Food steamed from the hickory-grained table. Bishop was fresh from the shower, spooning baked cabbage. Grabbing a buttered ear of corn. Then forking two fried pork chops onto his plate, wondering if his wife Melinda was waiting on him to confess his sins. What he’d been doing all summer after working at the furniture factory. What he’d ended today. The body he’d hid on the river bottom.

“Run into Fenton why you was wade fishin’?”

“No, why would I?”

Melinda stood next to the stove, twisted the burner knob and ignited the blue gas flame. Knelt down with a Lucky Strike between her lips and inhaled. Her hazel eyes looked into Bishop’s blue eyes. He thought maybe she could see the dead female’s soul floating within the glare of his sight.

“He’s supposed to go fishin’ this evening down on Blue River.”

“Didn’t see sight nor hair one, ain’t no tellin’ where that boy went fishin’. If he even went. Probably out drinkin’ with that Cecil boy again.”

“You’re one to talk, you been drinkin’ again.”

“So I had me a few, I’m forty four not twenty and breakin’ laws.”

“It’s the third time this week, used to be on the weekend.”

“Why don’t you worry about that boy and where he’s at. I ain’t bailin’ his ass out of jail again.”

“He should be home anytime, ain’t like he’d miss a meal his mother cooked.”

The screen door shrieked and slammed. Fenton stomped into the kitchen with his rusted brown layers of hair peeled back over his head. A face like Bishops when he was younger. Sanded to a smooth pale-wood finish. Only Bishop’s now bore the age of untreated graying wood, sanding it would only make it age quicker.

“Told you he’d not miss his mother’s cookin’.”

Bishop demanded, “Where you been, boy?”

“Drivin’.”

“Out with that Cecil boy again, don’t you work no more?”

Fenton’s boots trailed mud across the scuffed linoleum to the sink. Melinda shook her head. Fenton turned on the water and began lathering the bar of soap in his twitching hands. He’d driven the back roads of the county for the past hour. Trying to understand what his eyes had watched. Trying to make a decision. He’d come to one; he’d confront Bishop in front of Melinda.

“I was off from baggin’ groceries today and I went drivin’ alone around the county.”

“Where at around the county?”

Fenton hung the towel back on its hanger, imagining how cold that water must’ve been blanketing those forty year old bones. Just watching from the dying weeds had stiffened Fenton into a totem pole of panic. He turned and stared at this man he’d called ‘Father’ for twenty years. But the only word he knew to call him at that moment came harsh and outright.

“Down around Blue River….Murderer.”

Melinda stood blank-faced, hearing the word Murderer infect the kitchen’s air.

The madness Bishop’d discovered at Blue River grew into a swarm of bees, nurturing their nest of honey. Remembering the vehicle he thought he might’ve heard from above. The squeaking steering. Just like Fenton’s truck squeaked.

Constructing a smile instead of a smirk Bishop straight-eyed Fenton. Swallowed the chewed shards of pork chop. Spoke in the clearest tone he could muster.

“What the shit are you talkin’ about, you been out drinkin’ and drivin’ again ain’t you?”

Melinda demanded, “Fenton why you talkin’ crazy about your father?”

Not believing the reaction from Melinda or Bishop, Fenton stood confused by his own name. His lips formed an expression as though he’d ate a spoiled piece of fruit that rotted his insides. Bishop scooted his chair from the table, stood up.

And Fenton accused, “I seen you down in Blue River dragging…. ”

Approaching Fenton, Bishop focused on the bottle of Early Times behind him on the counter, cut him off with, “Boy you are as sick as they come, callin’ your father a murderer.”

“I seen what you did…”

Hard and rough as droughted earth Bishop’s palm drew blood from Fenton’s mouth. Bishop pinned Fenton against the counter. Ashes and tobacco dispersed as Melinda dropped her remaining cigarette to the linoleum. Bishop reached over behind Fenton to the counter. Grabbed the Early Times. Pushed it to Fenton’s face.

“Been nippin’ the bottle again ain’t you boy?”

Bishop inhaled the air from Fenton’s busted lip, turned to Melinda.

“I can smell it on him strong as fresh spread manure on a field.”

Quick as a copperhead’s fangs delivering venom to its prey Bishop balled his left hand into the chest of Fenton’s t-shirt. Swung him around in a broken circle and into the kitchen table that scooted across the linoleum, along with steaming food and ceramic plates. Fenton came quick from the table. Met Bishop’s backhand. Fear pushed him out the screen door. Blood warm like bacon grease dripped from his nose. He stepped to the gravel-mortared-surface of the sidewalk. Barefooted Bishop followed behind cursing,

“Run you spineless son of a bitch, run.”

Bishop twisted the lid from the bottle of bourbon. With a Walker hound’s bite he clamped down on Fenton’s shoulder, spun him around.

“You wanna drink, then have at it.”

Bishop flung bourbon into Fenton’s bloodied face. Stinging his nose and lips.

Melinda hollered from the kitchen, “Stop!”

Bishop hollered back, “Stay out of it.”

The madness from Blue River chewed through Bishop’s body. He punched Fenton off the sidewalk. In his mind Fenton was no longer his kin, he was like Christi, a threat. He’d remove his tongue or even kill him if that’s what it took.

Bishop clamped his left hand into Fenton’s throat. Slammed him against an elm tree within the yard. Fenton’s face boiled red. Air punched his lungs, rushed from his broken lips, expanding the hand that Bishop clamped around his throat.

Bishop turned the bottle upside down with his right, parted Fenton’s broken lips with his left, emptied the bourbon down Fenton’s blinking eyes and spitting lips.

“Like that boy? Wanna drink, come home disrespecting me, callin’ me a murderer. Get your mother all upset. I’ll teach you.”

“Stop you son of a bitch.”

Bishop dropped the bottle. Pulled his Case XX pocketknife from his pocket. Thumbed the single blade that had skinned and gutted many a coon, squirrel and rabbit.

“Say ahhh, boy!”

Fenton’s hands channel-locked around Bishop’s soup-bone wrist while he glanced down at the ground. Seen Bishop’s bare feet and he stomped.

Bishop cursed, “Bastard.” Dropped the knife. Stepped backwards. Lifting his feet as if standing on molten lead. Fenton followed him like a pig wallowing in shit.

Stomping his feet. Drove a fist underneath of Bishop’s jaw. Teeth gritted and chipped down onto tongue. Bishop spit blood thicker than brown gravy. Fenton grabbed the empty bottle of Early Times. Exploded it across Bishop’s face. Dropped him to the ground where he hunched on all fours. Shaking his head and spitting blood.

Fear and anger pumped Fenton’s heart. He raised his boot into Bishop’s ribs. Watched the red spit from his mouth. Fenton thought of the truck he’d parked down from Blue River, at the old barn used by Rudy Sawheaver for sheltering his hay. Then he walked down to surprise Bishop but instead he got the surprise. Seeing the body surface between his father’s legs, who stood knee-deep in the green river, his eyes bright and blinking, identical to a fireflies’ yellow-gooey-glow underneath in the night.

Hidden by the dying weeds, Fenton watched Bishop drag the body to the riverbank. Taking in glimpses of the pale female’s flesh, the flower print dress, drenched locks the color of soot that clung to her face. His vision blinked and pieced together glimpses of his father’s cousin.

Fenton kept driving his boot into Bishop’s ribs. The veins in the side of Bishop’s neck grew thick as earthworms discovered beneath rotted wood. He raised a single hand to his throat. His face swarmed into a fire barrel of red. He heaved and gasped. Fenton remembered Bishop dragging Christi’s body down the river current until he lost sight of him. Fenton stood within those weeds frozen by panic. Wondering why Bishop had murdered Christi.

Bishop twisted his graying madness up at Fenton who’d lifted his knee high. Drove his boot down into Bishop’s face and yelled, “Beg, you murderer. Beg and tell me the damn truth! Tell me why!”

Bishop’s outline turned into tilled soil, spread out face down without movement. Blood drew a puddle around the shape of his skull onto the cold earth. Fenton knelt to touch his neck. From behind, the wooden screen door slammed. A hard thud met the rear of Fenton’s skull. Vibrated a black pain throughout. Taking away his sight and kneeling posture. Dropped him to the earth beside his father. It was the butt of a .12 gauge, held by his mother Melinda, who stood questioning what her only child had done.

*

“It’s been over a week and that cousin of your father’s is still missin’.”

“Told you she’s in Blue River somewhere.”

“Boy we drug that river for two miles up one direction and two miles down the other. Through every bend and split they is. Ain’t found shit.”

“Told you I watched my father drag her from the river. Load her body with rock, wrap her with a log chain and drag her down the river.”

“I don’t buy that, if anyone killed Bishop’s cousin I believe it was you.”

“Why would I kill her?

“Got me, all I know is when we brought you in, you was whiskey-soaked belligerence.”

“Told you, father poured the whiskey on me.”

“Your mother’s sayin’ you come home drunk, accusin’ Bishop of murder. Says that you provoked him into a fight.”

“Provoked him? She’s crazy, it was self-defense.”

“Fenton my question is, if you watched Bishop drag his cousin down the river why didn’t you try to stop him? Or come to me?”

“Told you I was in shock, didn’t know what to do.”

Fenton stood with steel bars tarnished by the stink of slobbering drunks and wife beaters before him, dressed down in faded black and white county stripes. A bunk attached to the wall. The smell of piss from a single toilet behind him.

On the other side stood sheriff Koons in county kakis. Island of gray hair wrapping around the rear of his head. He’d time-lines pouched across his cheek bones. A gray handlebar mustache. He looked into Fenton’s tired baby blues, told him, “Let me tell you somethin’ Fenton, I’ve know’d Bishop for as long as people have driven automobiles in Harrison County. He’s a hardworkin’ son of a bitch. You on the other hand got caught drinkin’ with that Cecil boy a time or two and recently tore up the Mobil gas station’s bathroom. Got combative with my deputy. Add that to beatin’ your father into an incurable polio patient. You’re a loose cannon. Your words mean about as much to me as a champion racehorse with splintered joints and a bum hip. They’s useless. That’s why you’re bein’ charged with attempted murder.”

Koons turned away. Fenton fell back on the mattress that felt similar to the concrete. Cold and hard. Wondering what Bishop had done with Christi’s body.

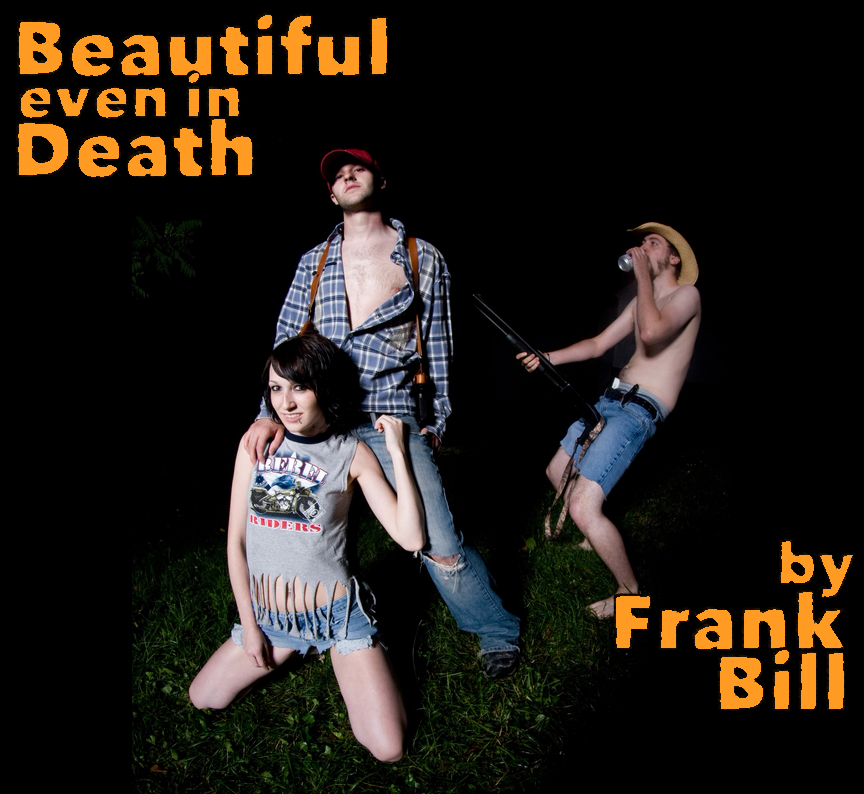

Frank Bill's work has been or will soon be featured in Thuglit (Issue 28), Plots With Guns (his home turf), Pulp Pusher, Beat to a Pulp (First ever double issue April 09), Hardboiled, Talking River Review, Lunch Hour Stories, and Darkest Before the Dawn. He lives with his beautiful wife Jenn and their two dogs, Jasmine and Malcolm.